What a tricky trait!

Back in the days, autism was understood by the layman as people “not being able to handle others”, or “not liking people”, or “being unable to connect to other people”.

This can be a reason why many would never have even considered having anything to do with autism – or any kind of “autism spectrum”.

Back in the days, the 1988 blockbuster movie “Rain Man” with Dustin Hoffman most probably only added to that huge dissociation of the autism spectrum reality and, by extension, led to the actual segregation of neurodiversity or neurodivergence altogether. Autistic people seemed to be extremely sick or lost poor individuals who are very far from any normalcy.

The topic of “sensory overload” can help to understand how this great misunderstanding could come about. So let’s dive in.

The neural networks in Aspies’ brains are wired differently. Among other things, in some areas and ways, they are more complex. Some findings say there are many more dendrites or connections between neurons or nerve cells.

Aspies tend to have more intense sensations. Noises might be louder, smells stronger, touch more touching, etc.

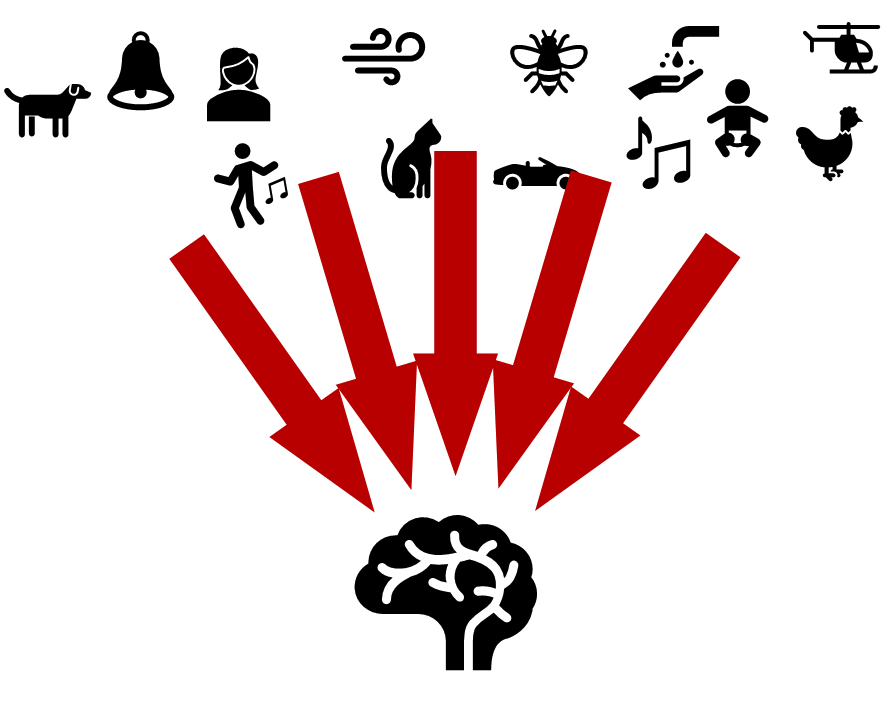

Here’s a simplified sketch of what happens when a non-Aspie has a conversation with another person in a noisy, tumultuous place:

All the sensory input, from the church bell ringing in a distance, to the helicopter buzzing by overhead, the wind bending the branches of the tree, the baby crying in the neighborhood, the dog barking across the street, and the cat pricking up its ears, is miraculously and efficiently filtered down to the only input that matters: the person across the table!

This happens thanks to a funnel that’s well designed by millions of years of evolution. Attenuate every input that’s irrelevant, reinforce the only thing that’s important. This way, the valuable brain resources are not wasted, and the species will survive.

To make the point, let’s consider the situation for a differently formed brain:

To an autistic brain, the sensory input might just flow directly into the brain completely unfiltered. The actually important input – the person across the table – is completely drowned out by all the others.

Make no mistake: this brain gets a much richer taste of life, for sure. It can get a huge lot more inspiration from even the dullest of situations. It can get high on regular life without taking any drugs. It can make discoveries others will miss. It can detect irregularities, it can develop feelings of bliss, ecstasy, deep emotions from even the most mundane scenes.

But in a demanding, at times stressful, overcrowded, dangerous, busy world, this can lead to total overstimulation:

That’s sensory overload.

As a result, the autistic brain – out of exhaustion or panic – might take a drastic measure and shut down:

It will just build a wall all around.

That’s when we get the classic “austistic person” who “can’t handle people” etc. as mentioned above.

The above diagrams are an exaggeration, but the dynamic can feel eerily familiar to an Aspie. It is put in motion in many situations great and small, and can often lead to the kinds of behaviors by the Aspie, or the response by the Aspie’s surroundings, that hurt so much.

It’s often not that the autistic person “doesn’t like people”, but to the contrary, that the autistic person gets so much sensory input by the presence or even the attention of an other person that it is overwhelming.

Solutions are often not to turn away from that tantrum throwing Aspie, but to help the Aspie just turn down the sensory inflow. In trauma therapy, “titration” is used to describe a way of reducing an exposure to manageable levels. This can be a good way to both avoid the actual overload while still enjoying the perks of a hyper sensitive nervous system.

There can be a special situation with late diagnosed Aspies: They tend to have learned that they must not shut down (not build the wall), ever. They might have trained themselves to avoid their (sometimes socially inacceptable) coping mechanisms and ignore their feelings of “this is too much”. With a result of sudden breakdowns or meltdowns: lashing out, screaming, doing other inacceptable, often shocking things all of a sudden. So the person who was always “so calm”, “so self reflected”, “so wise”, might suddenly explode with no advance notice.

This can be so traumatizing and off-putting to the others, that relationships can rip terminally.

In such cases, prophylactic reduction of sensory inflow even before any sensation of overload is well advised.